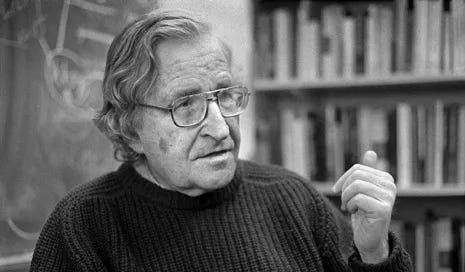

No Mic Podcast Scribed By Facelesslingjutsu - Profile: Noam Chomsky

Profiling Significant Figures or An Esteemed Guest

No Mic Podcast Scribed By Facelesslingjutsu - Interview: N. Chomsky By @mlaprise

·

25 Jan

Hey there!Thanks for reading No Mic Podcast Scribed By Facelesslingjutsu! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Within modern linguistics, it is chiefly within the last few years that fairly substantial attempts have been made to construct explicit generative grammars for particular languages and to explore their consequences. No great surprise should be occasioned by the extensive discussion and debate concerning the proper formulation of the theory of generative grammar and the correct description of the languages that have been most intensively studied. The tentative character of any conclusions that can now be advanced concerning linguistic theory, or, for that matter, English grammar, should certainly be obvious to anyone working in this area. (It is sufficient to consider the vast range of linguistic phenomena that have resisted insightful formulation in any terms.) Still, it seems that certain fairly substantial conclusions are emerging and receiving continually increased support. In particular, the central role of grammatical transformations in any empirically adequate generative grammar seems to me to be established quite firmly, though there remain many questions as to the proper form of the theory of transformational grammar. - Preface

Noam Chomsky, is an American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. Often called "the father of modern linguistics," he revolutionized the field with his theory of generative grammar and the concept of universal grammar, proposing that humans possess an innate capacity for language. This challenged the prevailing behaviorist views of language acquisition and sparked the "cognitive revolution" in the human sciences. Beyond academia, Chomsky is a prominent public intellectual, widely known for his critical analyses of U.S. foreign policy, contemporary capitalism, and the role of mass media and propaganda in shaping public opinion. He has authored over 150 books.

Noam Chomsky's early life, spanning his childhood in Philadelphia and his formative university years, laid the groundwork for his revolutionary work in linguistics and his enduring commitment to political activism. Born in 1928 to Jewish immigrant parents, William and Elsie Chomsky, both Hebrew scholars and teachers, Noam was immersed in an intellectually stimulating and politically aware household. His father, a respected professor of Hebrew, instilled in him a deep interest in language and scholarship, while his mother, active in the radical politics of the 1930s, fueled his early concern for social issues and justice.

Chomsky attended an experimental elementary school that fostered self-directed learning and creativity, a stark contrast to the more rigid academic high school he later experienced. This early educational environment, emphasizing individual exploration over competition, likely shaped his independent intellectual spirit. Even as a child, his political consciousness was keen; at the age of ten, he wrote an editorial for his school newspaper lamenting the rise of fascism in Europe after the Spanish Civil War, an early indicator of his lifelong engagement with global affairs.

By his early teens, Chomsky was independently exploring left-wing and anarchist bookstores in New York City, where he engaged with a vibrant intellectual community of working-class Jewish immigrants. These interactions, alongside his family's discussions on Zionism and various political ideologies, exposed him to diverse perspectives and solidified his anti-Leninist, anarchist leanings. He developed a strong aversion to Bolshevism from a young age.

At 16, Chomsky enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania, where he initially found his studies unstimulating. However, a pivotal encounter with the linguist Zellig S. Harris, whom he met through political connections, redirected his academic path. Harris, known for his work in structural linguistics, became a significant mentor, introducing Chomsky to the formal study of language and influencing his early research. Chomsky pursued his bachelor's and master's degrees in linguistics, focusing on the morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew, and later conducted research at Harvard. These early academic experiences, though sometimes marked by intellectual disagreements with his mentors (like Nelson Goodman, whose "blank slate" view of the mind Chomsky rejected), were crucial in developing his rigorous, logic-based approach to language and his nascent ideas about the innate nature of linguistic capacity, which would ultimately revolutionize the field.

After these foundational years, the immediate next phase in Noam Chomsky's intellectual journey was marked by his groundbreaking doctoral dissertation and the subsequent publication of works that truly revolutionized the field of linguistics. His PhD dissertation, "Transformational Analysis," completed in 1955 at the University of Pennsylvania, served as the initial, rigorous articulation of many of his radical ideas. In this work, he mounted a powerful and mathematically informed critique of the prevailing structuralist approaches to syntax, which he argued were insufficient for explaining the inherent creativity and complexity of human language. It was here that he first formally introduced the concept of "transformational rules," describing how sentences can be systematically rearranged from one structure to another, such as changing an active sentence into a passive one. While the full distinction between deep and surface structure would be more thoroughly developed later, the dissertation laid the conceptual groundwork for the idea that sentences possess an underlying, abstract representation of meaning from which various surface forms are derived through these transformations.

This foundational work then culminated in the widely influential publication of Syntactic Structures in 1957. Though a concise volume, it powerfully presented a formalized system of rules known as generative grammar that could account for the structure of all grammatical sentences, directly challenging the dominant behaviorist explanations of language acquisition, most notably B.F. Skinner's Verbal Behavior, which Chomsky would famously and critically review. Syntactic Structures further refined the distinction between a sentence's "deep structure," representing its abstract meaning and syntactic relationships, and its "surface structure," which is the actual sequence of words we speak or write. The book famously used the phrase "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously" to illustrate that a sentence could be grammatically correct even if it was semantically meaningless, thus underscoring the independent nature of syntax. This work is widely considered a pivotal moment in initiating the "cognitive revolution," redirecting academic focus from observable behaviors to the intricate internal mental processes that underlie human cognition, thereby influencing not only linguistics but also cognitive psychology, philosophy of mind, and even the nascent field of artificial intelligence.

Chomsky continued to elaborate and refine his theories, leading to what became known as the "Standard Theory" of transformational grammar, most comprehensively outlined in Aspects of the Theory of Syntax in 1965. This work significantly expanded upon the concepts of deep and surface structure, clearly defining deep structure as the underlying representation that captures the core meaning and grammatical relations, from which surface structures are derived through the application of transformational rules. Crucially, the concept of Universal Grammar (UG) became more central and explicit in Aspects. UG posits that all humans are born with an innate, species-specific linguistic endowment, a set of universal principles and parameters that guide the acquisition of any human language. This innate blueprint explains both the remarkable speed with which children master their native tongue and the fundamental structural similarities observed across the world's diverse languages. Chomsky also drew a critical distinction between "linguistic competence," referring to a speaker's subconscious, intuitive knowledge of their language's grammar, and "linguistic performance," which is the actual use of language in real-world situations, often imperfect and influenced by various non-linguistic factors.

From the late 1960s, Noam Chomsky gained prominence as a political activist alongside his linguistic work, becoming a leading critic of US foreign policy. He strongly opposed the Vietnam War, analyzing the role of intellectuals and media in justifying it, as seen in his book American Power and the New Mandarins. His critiques expanded to global US interventions, especially in Latin America, and he, with Edward S. Herman, detailed how mainstream media "manufactures consent" to serve elite interests, famously explained in Manufacturing Consent. Chomsky's political analysis covers diverse issues like the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, globalization, and capitalism, always using a fact-based approach to expose discrepancies in official narratives.

After establishing the Standard Theory, Noam Chomsky's linguistic work evolved through successive frameworks like the Extended Standard Theory and Revised Extended Standard Theory, aiming for greater simplicity and explanatory depth. This culminated in the 1980s with the Principles and Parameters Theory, which posited Universal Grammar as innate principles and settable parameters accounting for language variation. His pursuit of theoretical elegance and the solution to "Plato's problem" led to the Minimalist Program in the 1990s, striving to reduce linguistic theory to its most fundamental computational and biological principles.

In his political and social commentary, the 2000s and beyond saw Chomsky remain an extraordinarily prolific and consistent critic of global power dynamics, particularly following the September 11th attacks. He extensively analyzed the "War on Terror," arguing that it served as a pretext for expanding US military and economic influence, and he was a vocal opponent of the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. His work during this period, such as Hegemony or Survival: America's Quest for Global Dominance (2003) and Failed States: The Abuse of Power and the Assault on Democracy (2006), continued to dissect the history of US foreign policy, emphasizing the continuity of imperial ambitions under various guises. He broadened his focus to address emergent global crises, including climate change, nuclear proliferation, and the increasing concentration of wealth and power, often linking these issues to the systemic failures of neoliberal capitalism and unconstrained state power. He continued to advocate for active public engagement and popular movements as the primary means of achieving genuine democratic change and social justice. Despite his advanced age, Chomsky has maintained a rigorous schedule of writing, interviews, and public appearances, offering incisive commentary on contemporary events, from the Arab Spring and the rise of populism to the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East and the growing global inequalities.

As of mid-2025, Noam Chomsky is in his mid-90s and has recently been recovering from a "massive stroke" that occurred in June 2023, impacting his ability to speak.

I do not mean to suggest that linguists have all adopted Chomsky's views. They are still controversial, and he would be the first to acknowledge that they are subject to revision in the light of further evidence. Linguists who reject Chomsky's ideas, however, are trying to offer alternatives or to go beyond Chomsky. They are not turning back to Saussure. My point is not that Chomsky is right but that Saussure and Lacan are wrong. - Norman N. Holland, The Critical I (1992), Columbia University Press ISBN 0-231-07650-9, Chapter 30, "Lacan" pp. 192-208

It is important to understand just what properties of language were most striking to Descartes and his followers. The discussion of what I have been calling “the creative aspect of language use” turns on three important observations. The first is that the normal use of language is innovative, in the sense that much of what we say in the course of normal language use is entirely new, not a repetition of anything that we have heard before and not even similar in pattern – in any useful sense of the terms “similar” and “pattern” – to sentences or discourse that we have heard in the past. This is a truism, but an important one, often overlooked and not infrequently denied in the behaviorist period of linguistics to which I referred earlier, when it was almost universally claimed that a person’s knowledge of language is representable as a stored set of patterns, overlearned through constant repetition and detailed training, with innovation being at most a matter of “analogy.” - Chap. 1 : Linguistic contributions to the study of mind: past